Reflection on Mark 5:21–43

Phil Ruge-Jones | #EarlySermonSeeds

She reached out and touched his cloak. She told her story, and she was healed.

This is how Phil Ruge-Jones concisely told the story in his weekly social media posting of ‘early sermon seeds’.

She reached out and touched his cloak.

He turns, and turns, and asks again and again, who did this?

Is Jesus angry? [angry tone] who did this?! Is he concerned, or curious, or compassionate in response to a person in need? [kind tone] who did this? who needs me? Is he indignant at something being taken from him unasked? [indignant tone] who did this? how dare you?!

He turns and turns, asks and asks again.

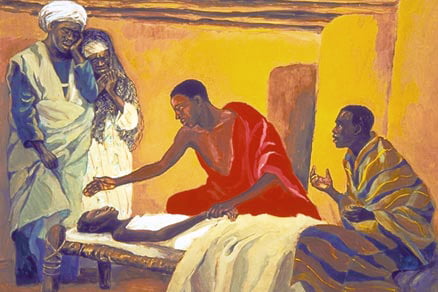

She comes forward.

He sees her.

She is afraid.

At what point might their eyes have met?

When she apologises? I imagine her head bowed at that point.

When she tells her whole truth? Perhaps her head begins to rise as she speaks, emboldened by the telling of her story, encouraged by his attentive listening?

Do their eyes not meet until he softens, and acknowledges her faith / faithfulness, and her being made well by it?

Are they looking at each other when they hear the message spoken to Jairus, your child has died? And what do they feel, what do they share, with each other in that moment?

Is she shocked, shamed at her healing costing another theirs? Is she confused, not understanding the broader events?

Is Jesus angry again, that his delay has prevented him from preventing the death of the child? Is he angry at the woman? Is he angry at himself, shamed, somehow, in his choice to stop on the way to Jairus’ house?

Is Jesus impatient with those who do not understand?

Perhaps if we were in John’s gospel, where Jesus’ divinity is emphasised, Jesus might be dismissive of humans who don’t understand the ways of God – he might be shown to know in himself the state of the child better than these humans.

But we’re in Mark, who emphasises Jesus’ humanity, so perhaps he is angry at himself, or the woman. Perhaps he is simply, sad for the child and her family.

Perhaps the sequence is that he hears the woman, is speaking with her about her truth, they hear the news, he lets go an expression of anger or disappointment, then their eyes meet, and he softens, stays with her in that moment, in her story, and blesses her act with his acceptance of it and her healing. Then he goes to the child’s bedside, endures the bitter laughter of the family and friends who think Jesus doesn’t know life from death, and wakes the child from her sleep.

Then Jesus tells them not to tell their story, which clearly didn’t work, did it? Someone told it.

Stories are intricate parts of the healing encounters people have with Jesus. Going from the moment and telling others of the miracle, the healing, the close encounter with the Sacred in Jesus (whether or not they’ve been told not to tell). Or telling Jesus the story of their illness, disability, disconnection from community, from life in its fulness.

Why Jesus stopped and turned and turned around in the crowd is unclear, and there seem to me to be several valid ways one could interpret Jesus’ motivation and feelings.

But why Jesus stopped and looked for who touched him with such purpose and effect, is not actually of interest to me today.

I am interested in the fact that he did stop, turn and turn and ask again and again, who did this? Who took healing from me? That he looked for the person. And that he listened to her story.

Whether he was miffed, curious, startled, angry, he looked for her, looked at her, and he listened.

She told her story, and she was healed.

There is a reason story telling is so often part of the stories of healing. There is a reason the life of Jesus is told in story. Why Jesus himself uses story to teach, to evoke an understanding of the kin-dom of God.

Daniel Taylor tells us: ‘Stories engage everything about us – mind, emotions, spirit, imagination, body, and more. Therefore nothing in life has more power to shape us than stories.’[i]

‘Stories are fundamental to human well-being.’[ii] Because stories tell us who we are – as we tell our own, and as we receive the gift of the stories of others.

As we tell stories, and reflect on them, ‘we generate insight and help clarify’ meaning in our lived experience.[iii] If we tell someone what to believe, they may or may not agree with us: but when we tell story, we absorb it, and live with it, and it nurtures our wellbeing.[iv]

Now, ‘the Bible, like all sacred texts, understands that storytelling is [for example] the primary vehicle for preserving and passing on faith … Israel is called to faith not in an abstract concept called God, but in the God who “rescued you out of Egypt,” that is, in the God who acts – as recorded in stories. We are called to … to tell the stories of, among other things, God acting in our lives.’[v] And it seems that call overrides any command even from Jesus to refrain from telling those stories.

It is not only for the benefit of others that we must tell our stories. Telling my story and being heard is a fundamental part of the stories of healing encounters with Jesus because the act of telling our story and being heard is itself healing. We become ourselves as we tell our stories, and when our story is heard it nurtures our self, our becoming, our wholeness. Social and Church researcher, Diana Butler Bass, observes that telling our stories of encounter with God ‘speaks of God making wholeness out of human woundedness.’[vi] And ‘in telling the stories of our lives, we find we are not alone.’[vii]We offer to each other, and ourselves, wisdom, resources for living, or simply, in the act of shaping stories, connection with one another, which is also profoundly healing.

Story. Humans are story – or storied – beings. It is vital for our wellbeing that we practice the discipline of story, telling the stories of our lives. We do it naturally every day. And we need sometimes to reflect on our stories, to craft and polish them into a shape in and through which they will be well received.

Practices of oral storytelling; of writing – stories, journals, poetry, letters; compiling memory boxes or scrapbooks. There are so many ways we can share our stories with each other, tell them and reflect on them for ourselves.

We are going to start practicing the discipline of telling our stories here at Wesley, later this year. Please watch for the invitations, and do please participate when the opportunities arise. Telling and hearing, giving and receiving stories strengthens a community and by leading us to better health individually and together.

She reached out and touched his cloak. She told her story, and she was healed.

May we also reach out to touch Jesus. May we, too, have the courage to tell the truth of our own story, and find healing for ourselves, and together. Amen.

Leave A Comment